Amortised analysis in a few words

If you are a software engineer like me, you might have in your home a bookshelf proudly filled with colossal textbooks covering various programming languages, computer science subfields, or software principles. I’m not sure how much the average programmer spends reading physical technical books in this era of abundant online resources, but I am certainly guilty of having spent too little time digging into them. A few years after finishing uni, I found myself missing the process of deep-diving into a technical topic just for the sake of learning something new. I also realised that my knowledge of CS fundamentals didn’t expand much past the standard requirements to land a job in tech, and I figure it might be time for an upgrade.

I decided to give a shot to Introduction to Algorithms by Cormen, Leiserson, Rivest and Stein, a comprehensive textbook that, contrary to what the name would suggest, goes well past the introduction phase and dives deep into all the classic algorithms and data structures (and also some not so classic ones), with a rigorous yet accessible approach.

Last week, I read about amortised analysis and I found myself pleasantly surprised by how neat and approachable that particular section was (worth noticing that it was shortly after reading the chapter on red-black trees). In this post I’ll try to summarise the key takeaways from my reading.

What is amortised analysis about?

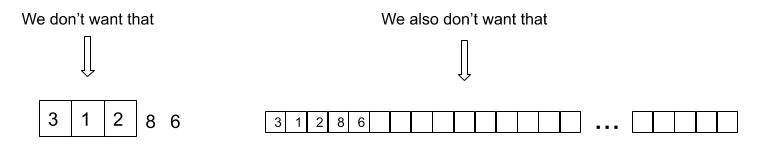

The textbook example to explain what amortised analysis is the example of a dynamically resizable array. We don’t know how many elements will be stored in the array (it could be a lot), but we also don’t want the array to be wasting lots of unused space in memory. We can address this by starting with a small size and reallocate chunks of memory when needed, for instance by doubling the size of the array every time we reach full capacity.

This means that some array operations that used to be O(1) in the worst case like insertion now have a worst case complexity of O(N) because they could trigger a resizing operation which runs in O(N) time. Naively, one could infer that a sequence of M insertions on the array now have a worst-case complexity of O(N*M) because each insertion could technically cost O(N). Intuitively we know the limit is tighter because resizing operations will happen only occasionally. The cost of the occasional resizing is “amortised” across the series of insertions that precede and follow it, which themselves still run in O(1).

How can we formalise this and apply the reasoning to other types of problems? This is where amortised analysis comes in. Instead of considering the average case and the worst case of the insertion operation, we assign to it an “amortised” cost that accounts for the occasional resizing.

There are two methods presented in the book to determine the amortised cost of an operation: the accounting method and the potential method. I will quickly introduce each.

Determining the amortised cost of an operation: the accounting method

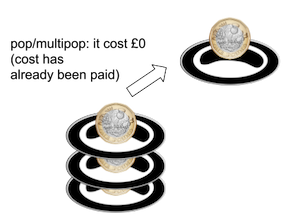

To illustrate the accounting method, we are going to use the example of a stack supporting three operations: the usual push and pop and also a multipop operation which removes multiple elements at once. Intuitively, the worst case cost of multipop (which is hit when we are removing all the elements of a non empty stack) is O(N), N being the number of elements in the stack. Again, we could infer from this that any sequence of N push, pop and multipop operations has a worst case of O(N^2), since we may have N multipop operations costing O(N) each. In fact we can prove with amortised analysis that this sequence of operations will run in maximum O(N) time, by assigning a constant amortised cost to each operations. We can assign a cost of 2 for the push operations, and 0 for pop and multipop. Let’s see how this would work.

Imagine that you’re in a cafeteria with a stack of plates and some £ coins to represent the cost of each operation (I live in the UK and I insist on this being a British cafeteria). You start with an empty stack of plates. Every time you put a plate on the stack, you “pay” a cost of £2, £1 is used to pay the cost of pushing the plate, and you leave the remaining £1 on top of the plate. You can consider the £1 left on the plate as “prepayment” for the cost of popping the plate later on. Every time you execute a pop operation, you take the £1 credit off the plate and use it to pay the cost of the popping operation. Whether you’re popping plates individually through pop or collectively through multipop, the cost of the operation has been prepaid for each plate by the push operation that initially placed it there.

Therefore allocating a slightly higher (but still constant) cost to the push operation, we’ve allowed ourselves to make pop and multipop free. This means the amortised cost for a sequence of N push, pop and multipop operations is bounded by the cost of N push, which is O(N).

Determining the amortised cost of an operation: the potential method

The potential method introduces the concept of a “potential function” associating a “potential energy” to the data structure as a whole rather than a cost to individual objects inside it. This energy can be used to pay for future potentially (pun intended) costly operations. People with a physics background might notice a parallel with classical mechanics.

Let’s name this potential function Φ. The amortised cost ĉi of the ith operation on data structure D is defined as the cost of the operation c(i) plus the difference of potential before and after the operation. In other words, ĉi = ci + (Φ(Di) - Φ(Di-1). From this, it follows that the amortised cost for a series of n operations is:

∑(ĉi) = ∑(ci + (Φ(Di) - Φ(Di-1))

= ∑(ci) + Φ(Dn) - Φ(D0)

where the Φ(Di) terms cancel each other because of telescoping.

Therefore if we can find a function Φ so that Φ(Dn) >= Φ(D0), we can use it to get an upper bound on the cost of this series of N operations, which is what we were trying to determine in the first place.

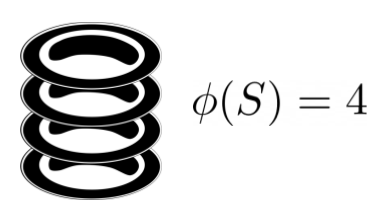

If we go back to our stack example, the potential function can be defined simply as the number of objects contained in the stack.

Trivially Φ(S0) = 0 and Φ(Sn) >= Φ(S0) whatever n we choose, our initial requirement for Φ is therefore satisfied.

The amortised cost of a push operation on stack S becomes ĉi = ci + Φ(Si) - Φ(Si-1) = 1 + 1 = 2 as the difference of potential after and before the operation (aka Φ(Si) - Φ(Si-1)) can be reduced to the difference in the number of objects contained in the stack before and after the push operation which is 1. A symmetric reasoning for popping gives us an amortised cost of ĉi = 1 -1 = 0. For a multipop of k elements, the cost ci of the operation is at most k and the difference in the number of objects before and after the operation is at most -k, so we also get an amortised cost of ĉi = k - k = 0.

Therefore the potential method has proven that the amortised cost of each of the stack operations is constant, yielding a maximum cost of O(n) for a series of N push, pop and multipop. We are back on our feet!

Amortised analysis on a dynamically resizable array

Let’s go back to our very first example of the dynamically expandable array. A common approach for dynamic expansion is to double the size of the array when reaching full capacity and contract it by half when the “occupation rate” is under 50% (this contraction strategy is actually suboptimal when hitting a particular sequence of insertion and deletion, I’ll go back to this later). Therefore the amount of “wasted space” never exceeds half of the total space in the array.

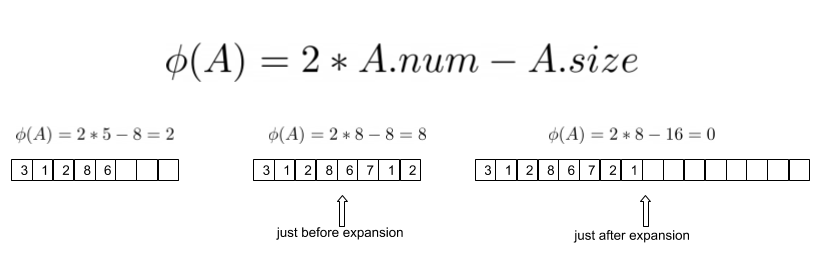

To determine the amortised cost of inserting and deleting from the array T, we can use the potential function Φ(A) = 2 * A.num - A.size where A.num represents the number of elements in the array and A.size is the size allocated for the array.

First of all, does Φ meets our requirement that Φ(An) >= Φ(A0)? We start with 0 elements and a size of 0 which trivially gives us Φ(A0) = 0. Since we know that the array is always at least half full, we know that the quantity (2 * A.num - A.size) is always non negative, which confirms Φ(An) >= Φ(A0) for any n. Now that we’ve got the suitability of Φ as a potential function out of the way, what amortised cost does it give us for the insertion operation?

If the insertion does not trigger an expansion, A.size does not vary and therefore the amortised cost can be computed as:

ĉi = ci + Φ(Ai) - Φ(Ai-1) = 1 + ((2 * A.numi - A.sizei) - (2 * A.numi-1 - A.sizei-1)) = 1 + 2 * A.numi - A.sizei - 2 * (A.numi - 1) + A.sizei = 3

.

If the insertion does trigger an expansion, then A.sizei = 2 * A.sizei -1, and we also know that A.sizei-1 = numi - 1 because the array was in full capacity before the expansion. The amortised cost is then

ĉi = ci + Φ(Ai) - Φ(Ai-1) = 1 + ((2 * A.numi - A.sizei) - (2 * A.numi-1 - A.sizei-1)) = 1 + 2 * A.numi - 2 * (numi - 1) - 2 * (A.numi - 1) + 2 * (numi -1) = 3

.

We have now formally proved that the amortised cost of an insertion operation on a dynamically expandable array is constant!

As I mentioned before the strategy we chose for the array contraction does not actually yield a constant amortised cost for the deletion operation in the worst case. A better strategy is to halve the table size when the “occupation rate” is under 25% rather than the previously chosen 50%. This complexifies slightly our choice of Φ, so I won’t cover the details here. If you’d like to know more, by all means get yourself a copy of Introduction to Algorithms and open chapter 17.4.2!

Final thoughts

This kind of topics is what I like the most about CS. It’s substantial enough to require some brainpower but it’s also very approachable, you can make analogies with the real world, and the maths behind it are simple and elegant!