Transitive closure of a dynamic graph

Hi there, it’s been a few months since my last post!

I have to admit, the motivation for starting this website emerged, to a certain extent, from the necessity to find lockdown friendly pastimes. But as stuff started to reopen over the summer, writing has been displaced by other distractions. The acquisition of an Xbox at the end of the spring was admittedly another contributing factor. But as it looks like we’re heading back into a full lockdown situation, what better time to pick Introduction to Algorithms right back up and do some problem solving!

I have now been diving into the world of graphs, one of my favourite topics in computer science. Most elementary graph algorithms are elegant and easy to grasp, and they have so many applications in the real world: GPS, cell towers, computers operating systems, Google search page ranking… The world runs on graph theory.

I’m not going to write an implementation of Dijkstra, Prim or Kruskal here, there’s already countless examples out there. Instead, here’s my attempt to solve a small problem related to transitive closures, found in chapter 25.

Transitive closure of a simple graph

The transitive closure of a directed graph G can be simply defined as an “extended” version of G, where there is a direct edge for every pair of vertices that have a path in G.

Formally, that translates into: For a given graph G = (V, E), the transitive closure of G is defined by G*(V, E*) where E* = {(i, j) : there is a path from i to j in G}.

We can also represent the transitive closure of a graph as a boolean matrix defined by tij = 1 if there is a path from i to j in G, and 0 otherwise.

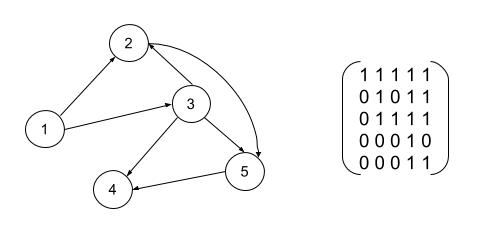

Here is a simple graph and its transitive closure matrix:

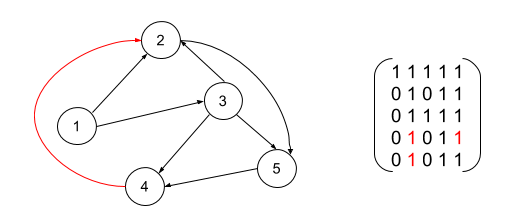

If we add a new edge from vertex 4 to vertex 2, the transitive closure will now contain a few more 1s.

So how do we maintain the transitive closure of a graph as we insert new edges?

For any newly added edge (u, v), we just need to indicate that all the vertices that currently have a path to u will now also have a path to all the vertices that currently have a path from v. Nothing that a double for loop over all of vertices can’t solve:

#!/usr/bin/env python

def updateTransitiveClosure(transitive_closure, u, v):

for i in range(len(transitive_closure)):

for j in range(len(transitive_closure[i])):

if transitive_closure[i][u] and transitive_closure[v][j]:

transitive_closure[i][j] = 1

def main():

transitive_closure = [[1, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 0, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[0, 0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 1, 1]]

updateTransitiveClosure(transitive_closure, 3, 1)

expected_transitive_closure = [[1, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 0, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 0, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 0, 1, 1]]

assert transitive_closure == expected_transitive_closure

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

updateTransitiveClosure runs in O(V2) as we iterate over all of the matrix elements.

There is at most O(V2) edges we can insert into the graph, so if we keep adding edges until the graph is strongly connected, the overall runtime will be O(V4).

A more efficient algorithm

Nice, but there is room for improvement.

In the example above, the first 3 rows of the transitive closure matrix didn’t get updated. This is actually something that we could have predicted before even running the algorithm. Note that vertices 1, 2 and 3 already had a path to vertex 2 before adding edge (4, 2). That means that there can’t be any vertex newly accessible from 1, 2 or 3 as a result of adding (4, 2), because these would have already been accessible prior to adding the edge.

We can easily incorporate this obervation into the algorithm:

#!/usr/bin/env python

def updateTransitiveClosureBetter(transitive_closure, u, v):

for i in range(len(transitive_closure)):

if transitive_closure[i][u] and not transitive_closure[i][v]:

for j in range(len(transitive_closure[i])):

if transitive_closure[v][j]:

transitive_closure[i][j] = 1

def main():

transitive_closure = [[1, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 0, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[0, 0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 1, 1]]

updateTransitiveClosureBetter(transitive_closure, 3, 1)

expected_transitive_closure = [[1, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 0, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 0, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 0, 1, 1]]

assert transitive_closure == expected_transitive_closure

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Now this still runs in O(V2), but the amortised complexity is improved.

The outer loop will be run at most O(V2) times so its overall cost is O(V3).

The inner loop is run at most O(V2) times in the overall sequence insertion. This is because, after each execution of this loop, there is at least 1 element in the transitive closure that will be set to 1. After a max of O(V2) execution of this loop, all the elements will have been set to 1 and the loop won’t be run again. As a result the inner loop has an overall cost of O(V3).

updateTransitiveClosureBetter therefore yields an amortised runtime of O(V3), neat!