Ray Tracer I

As mentioned in a previous post, I have spent some timer earlier this year learning about computer graphics with scratchapixel, and giving a shot at writing my own ray tracer.

In this article I won’t go into into explaining what ray tracing is. This would deserve its own post and I couldn’t do a better job than scratchapixel intro to ray tracing anyway. What’s really cool about ray tracing is that it’s not merely a technique to produce compelling images, it actually closely follows the “real world” process of how light travels from light sources to our eyes. While working on this project, I’ve learnt as much about physics as I did about computer graphics. The fact that ray tracing mirrors the laws of nature is one of the reasons it’s computally expensive, but look at what it can produce:

The above was generated entirely with ray tracing (credits to Enrico Cerica). Admire the effects of the glass distortion inside the lamp, the glass rendering in the window, and just the general realism of the scene. Not surprisingly, the ray tracer I wrote is lightyears away from something like this. In fact, it can only generates spheres and only supports diffuse lighting (when light reflects equally in all directions). But as in any project, if you want to get anywhere you have to start small.

Scratchapixel has been an invaluable guide in this endeavour and I basically owe them everything I know about ray tracing. Naturally, the way my code is organised from a high level perspective bears a few similarities with the ray tracer code that they provide on the website. The code to produce the .ppm file and compute the camera angles are very close to theirs, and I have also plainly copy pasted their matrix and vector classes as I considered that mostly boilerplate. However, I’ve really strived to write the rest of this code and especially the main logic in my own way, by putting into practice the coding principles that I hold dear. This means that I sometimes departed from their guidelines, sometimes looked elsewhere for help, sometimes made mistakes. But as a result, I’m glad to say that this is a project I feel like I really own.

Without further ado, let’s look at the internals of this ray tracer!

Personal touches

In the following sections I’ll briefly discuss some of the coding style decisions I made.

A generous amount of types

I’m a strong supporter of encapsulating related entities into lightweight types. If a function needs to return more than one variable, I’ll create a struct long before I even think about output arguments. If I ever end up passing around the same bunch of variables more than once, I bundle them into a struct. And if two types of object can be encoded with same data type but represent different concepts, they’ll each get their own struct or class.

This has led me to create a whole bunch of plain, lightweight types to represent most concepts associated with ray tracing: rays, intersection points, intersected objects, light, pixels, colours. Even if a pixel and a colour can both be represented with RGB values, I figured the colour of an object is semantically different than a pixel on my screen so they are defined as separate types.

Modern C++ to the rescue

I am grateful to live in an era where std::optional is a thing and my life as a developer would certainly not be the same without it. Be gone, special values, output parameters and booleans to indicate if some variable has been set.

I also systematically manipulate addresses through smart pointers, this valuable language feature who allowed so many developers to sleep better at night with the comforting thought that all the memory they allocated that day had been rightfully freed.

Something where I’ve found std::optional to significantly improve the readability of the code is to compute the intersection of a ray with the nearest object. There might not be such an object in the ray’s trajectory, which is why the function that performs this task is suggested with the following signature:

class Object {

// Intersect ray defined by orig and dir with object

// If intersection, populate tnear with intersection point and return true (normal is not returned)

// If no intersection, return false

virtual bool intersect(

const Vec3f &orig,

const Vec3f &dir,

float &tnear,

uint32_t &index,

Vec2f &uv) const = 0;

// Rest of the class definition ...

};

bool trace(const Vec3f &orig, const Vec3f &dir, float tNear, Object **hitObject)

{

// Compute intersection of ray with origin 'orig' and direction 'dir' with nearest object

//

// If there is an intersection, return true and populate tNear with nearest intersection point

// and hitObject with nearest intersected object

// If there is no intersection, return false

}

I replaced that with:

// Type definitions

struct Ray

{

Point origin;

Vec3 direction;

};

struct Intersection

{

Point p;

Vec3 normal;

};

struct IntersectedObject

{

std::shared_ptr<Object> object;

Intersection intersection;

};

class Object {

// Get intersection (point + normal) of ray with object

// If no intersection, return nullopt

virtual std::optional<Intersection> Object::getIntersectionWithRay(

const Ray &ray);

// Rest of the class definition ...

};

std::optional<IntersectedObject> getNearestObject(

const Ray &ray, const std::vector<std::shared_ptr<Object>> &objects) {

// For each objects, call getIntersectionWithRay

//

// If intersection, set IntersectedObject to nearest intersected object

//

// If no intersection, return std::nullopt

}

Of course there is a small overhead with using wrapper types such as those custom struct, optionals and smart pointers. It makes virtually no difference for now, but if I extended this ray tracer to compute increasingly complex scenes, maybe I’d find that this cost is too high to pay, and maybe that’s why the code provided in scratchapixel keeps this overhead to the bare minimum. At the moment, I feel like the readability boost is absolutely worth it, but I say this as an application developer who work on distributed systems where the bottlenecks are typically dictated by the number of network round trips and the efficiency of the data stores, not by how optimised the C++ code is. In computer graphics and ray tracing in particular, the same intersection routine might be invoked for millions of rays and objects in a single image, so that’s when small optimisations start to make a difference.

That’s one of the cool things about learning a different software domain, it puts into perspective your own rules about what’s good code and what’s not.

A dark scene

After a few coding sessions, I had the high level logic written down as well as the supporting features such as randomly generating a scene and writing the pixels to a file. I was ready to admire the product of my work, which would be a beautiful assortment of spheres of varying sizes and colours, floating in a black void and casting shadows on each other. I build the project, run it, open the scene and this is what shows up in my screen:

A bit underwhelming isn’t it?

We can vaguely distinguish the outline of a few spheres here, but something is clearly off. None of the spheres are “fully” coloured, at best one half of an edge is somewhat visible but the rest is pitch black. I initially thought that my light sources were misplaced, or that something was blocking the light from propagating. But even after playing around with lots of different light positions, scene dimensions or reducing the sphere count to one, my images were desperately dark. Not a single sphere was produced in its entirety.

I asked another engineer for help. He and I dissected the code for a bit and our attention was brought to the shading function.

The shading function is responsible for determining the colour of a pixel once you have established that the camera ray associated to that pixel intersects with an object. You cast a ray from that intersection point to all the light sources and invoke the getNearestObject routine again to understand if the object is in the shadow of another object. If it is, the contribution from that light is discarded. If not, the light contribution is incorporated to the final colour, in this case using the Phong illumination model (the Phong model also handles specular reflection but my ray tracer only supports diffuse reflection for now).

This is what my shading function looked like, and just below the ray casting function that invokes it:

Color shade(const IntersectedObject &intersectedObject, const Ray &ray,

const std::vector<std::shared_ptr<Object>> &objects,

const std::vector<std::shared_ptr<Light>> &lights)

{

const Intersection &intersection = intersectedObject.intersection;

float lightIntensity = 0;

float specularColor = 0;

for (const std::shared_ptr<Light> &light : lights)

{

Ray shadowRay{

intersection.p, Vec3(light->position - intersection.p).normalize()};

// Check if object is in the shadow of another one

std::optional<IntersectedObject> nearestObject =

getNearestObject(shadowRay, objects);

if (nearestObject.has_value())

{

float shadowObjectToLightDist =

Vec3(nearestObject.value().intersection.p - light->position)

.norm();

float objectToLightDist =

Vec3(intersection.p - light->position)

.norm();

if (shadowObjectToLightDist < objectToLightDist)

{

continue;

}

}

lightIntensity +=

(light->brightness * std::max(

0.f, shadowRay.direction.dotProduct(intersection.normal)));

Vec3 reflectionDirection =

getReflectionDirection(

shadowRay.direction * -1, intersection.normal);

specularColor +=

powf(

std::max(

0.f,

-reflectionDirection.dotProduct(ray.direction)),

SPECULAR_EXPONENT) * light->brightness;

}

return intersectedObject.object->color

* lightIntensity * KD

+ specularColor * KS;

}

Pixel castRay(const Ray &ray,

const std::vector<std::shared_ptr<Object>> &objects,

const std::vector<std::shared_ptr<Light>> &lights,

const Options &options)

{

std::optional<IntersectedObject> nearestObject =

getNearestObject(ray, objects);

if (!nearestObject)

{

return Pixel{options.backgroundColor};

}

Color pixelColor = shade(nearestObject.value(), ray, objects, lights);

return Pixel{pixelColor};

}

There is something critically missing in the previous piece of code, which was spotted by my fellow engineer.

When checking whether the object is in the shadow of another object, I’m passing down to getNearestObject the entire set of objects composing the scene including, critically, the original object itself. This is problematic because, unless the intersection point is the object’s closest point to a given light source, that same object will most likely intersects the shadow ray that we cast towards that light source. In other words, the object will be in the shadow of itself.

The good news was that fixing this is a four line change. Just adding the following snippet at the beginning of the shade function did the trick:

// Filter out intersected object from the object array so that we don't intersect it with itself

std::vector<std::shared_ptr<Object>> otherObjects;

std::copy_if(objects.begin(), objects.end(), std::back_inserter(otherObjects),

[&intersectedObject](const std::shared_ptr<Object> &obj)

{ return obj != intersectedObject.object; });

// Use 'otherObjects' when invoking getNearestObject with shadow rays

Let there be spheres

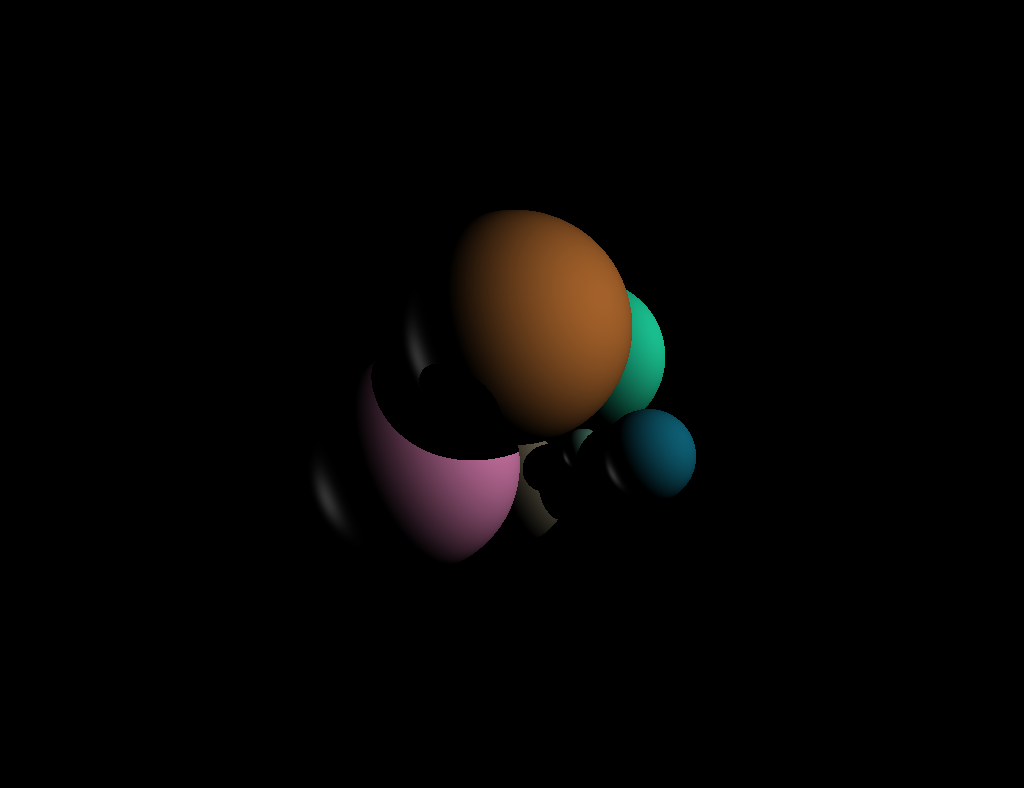

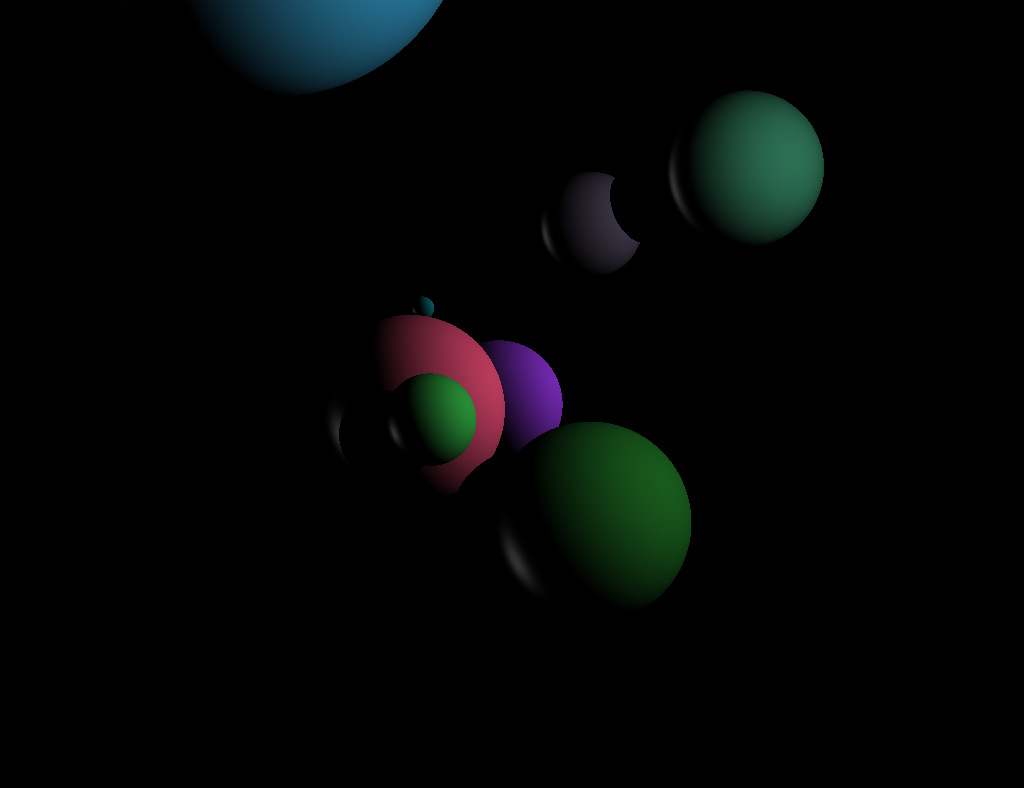

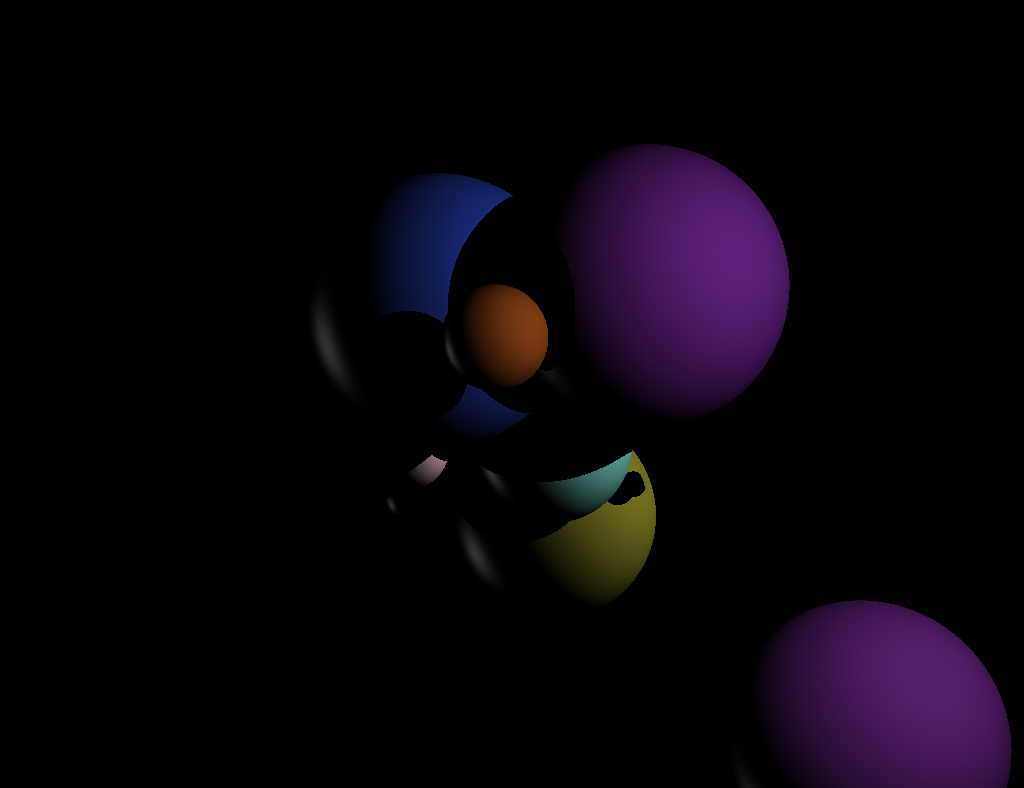

After incorporating the fix discussed above, this is what got generated:

Now that’s more like it!

I never thought a bunch of floating spheres could provide much excitement but on that moment, it really did. Needless to say I spent the next ten minutes re-running the program and admiring a selection of randomly generated outputs.

Here is a sample:

Next steps

While it’s thrilling to see your first ever ray tracing shape coming to life on the screen, the excitement generated by a bunch of diffuse spheres can only last so long. But there are many fun things that I want to add to this: specular reflection, transparency, glass distortion, support for new shapes (especially triangles and polygon meshes). In addition, I’d also like to learn about rasterization (ray tracing’s main rival on the rendering scene) and maybe take a shot at writing one too. The journey inside the world of computer graphics has only just started! ![]()

Oh and if you want to check out the code, here is a link to the repo.