Amortised analysis on a disk stored stack

Following up my previous post about amortised analysis, I am going to apply it to a problem drawn from the B-Trees chapter in Introduction to Algorithms.

Here we are considering a stack too large to fit in memory, and the cost of maintaining suck a stack through various paging strategies. Amortised analysis will be used in the last section to evaluate this cost.

A few words about memory and paging

We don’t need to go into great details about memory management to solve this problem but let’s just recap the fundamentals to make sure everyone is on the same (pun unintended) page.

Computer memory is divided between main memory (the RAM) and secondary memory (the disk).

Main memory consists of silicon chips made of lots of transistors, and by lots I mean billions. Each transistor is paired with a “memory cell” that contains a bit of information. The memory cell is a capacitator (you can think of it as a tiny battery) wich represent a 1 when filled with electrons and a 0 when empty. The transistor acts as a switch on the capacitator. Any read or write operation is based on electricity flowing through an electronic circuit. Therefore, RAM access is very fast, it’s nanoseconds fast. But it’s also volatile, the data disappears as soon as you cut power. Besides, RAM is also expensive.

That is why computers also have a secondary storage.

For a few decades we used hard disk drives (HDD) as secondary storage. Hard drives are essentially on magnetic platters rotating around a spindle. These platters are divided into billions of tiny areas that contain either a 0 (unmagnetised cell) or a 1 (magnetised cell). Each platter is read and written with a magnetic head at the end of an arm. The arms can move their heads towards or away from the spindle. To read or write a cell, we need the arm’s head to reach that cell which involves two mechanical movements: the platter rotation and the movement of the arm itself. To reach a particular cell, you might have to wait for a full platter rotation which is in the order of milliseconds. Because disk access is based on mechanical movements, hard drives are slow.

In recent years hard drives have been supplanted with solid state drives. Just like RAM, these are based on integrated circuits and are therefore much faster than disk. Unlike RAM, the memory is non volatile which means you can persist it when the power is off. It’s still not nearly as fast as RAM because of the data throughput capacity between the drive and the motherboard.

In order to optimise the time spent on mechanical movements (for HDD), or data transfer, disks access not just one element at a time but several. Information on a disk is divided into equal size blocks of bits, called pages.

For the rest of this article, we will refer to “disk access” as the number of pages that need to be read and written to the disk.

A stack entirely stored on disk

Back to our stack.

Let’s first consider a stack entirely kept on disk. We maintain in memory a stack pointer, which contains the disk address of the top element on the stack. If the pointer has value p, the top element is the (p mod m)th word on page ⌊p/m⌋ of the disk, where m is the number of words per page.

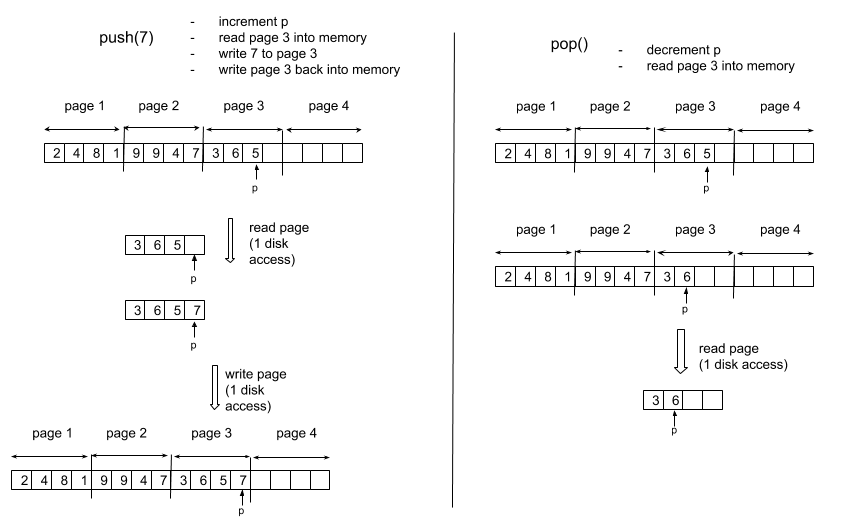

To implement the PUSH operation, we increment the stack pointer, read the appropriate page into memory from disk, copy the element to be pushed on the appropriate word on the page, and write the page back to the disk. For the POP operation, we decrement the stack pointer, read in the appropriate page from disk, and return the top of the stack . Note that we don’t need to “clean” the value previously held in memory as it will get overwritten anyway if we use that cell again, but for clarity I will blank the “popped” cell in the following illustrations.

push and pop on a disk stored stack

Any disk access to a page of m words has a CPU time of O(m), since m words must be read into memory.

A push operation includes 2 disk access and a pop operation has 1 disk access. Any combination of n stack operations has therefore a CPU time of O(n*m).

One page in memory

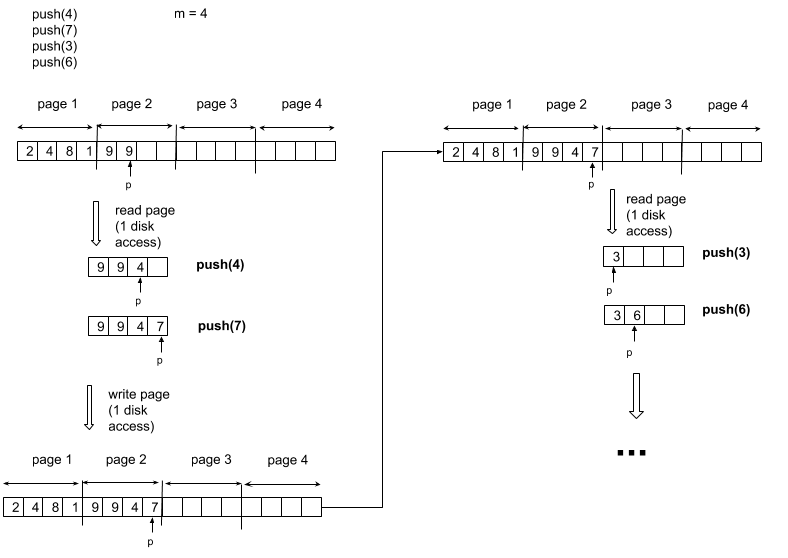

We now consider stack implementation in which we keep one page of the stack in memory. We can perform a stack operation only if the relevant disk page resides in memory. When necessary, we can write the page currently in memory to the disk and read in the new page from the disk to memory. If the relevant disk page is already in memory, then no disk access is required.

What is the CPU time for a series of n PUSH operations? One PUSH operation has a cost of either 1 disk access (when the current page is full and we need to load the next one) or no disk access at all when we can write into the currently loaded page. The disk access frequencyis of n / m where m is the number of words per page. A series of n PUSH incurs therefore a cost of n / m disk access costing O(m) each, which brings us to a worst case cost of O(n).

n push on a stack with the one-page implementation

We can apply a symmetric reasoning for a series of n POP.

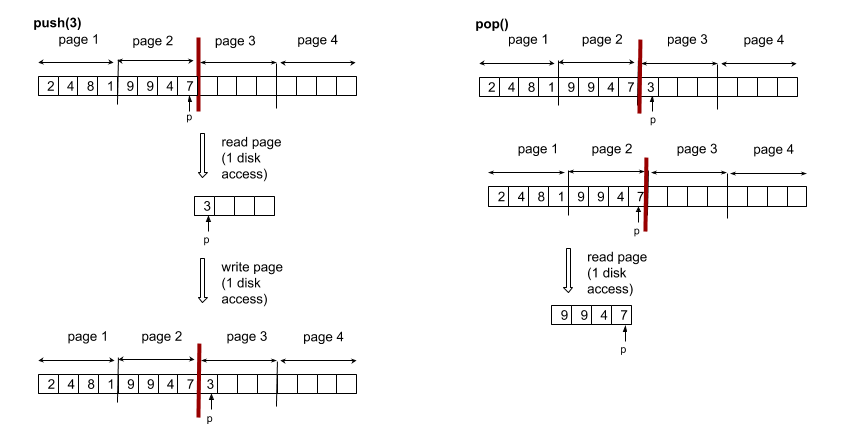

But what about a series of n PUSH or POP operations. You might be tempted to think, based on the above, that we will also end up with a cost of O(n). There is actually a worst case scenario where we are back to a cost of O(n*m). Consider a series of PUSH-POP-PUSH-POP-… on the boundary of a page. Essentially the two operations shown below repeated over and over.

push and pop at the page boundary

Now it is clear that each operation introduces at least 1 disk access and therefore the sequence has a cost of O(n*m). That means that the amortised cost of a push or a pop is not constant.

Two pages in memory

Let’s now suppose that we can implement the stack by keeping two pages in memory. Can we find a way to achieve a constant amortised cost for any stack operation?

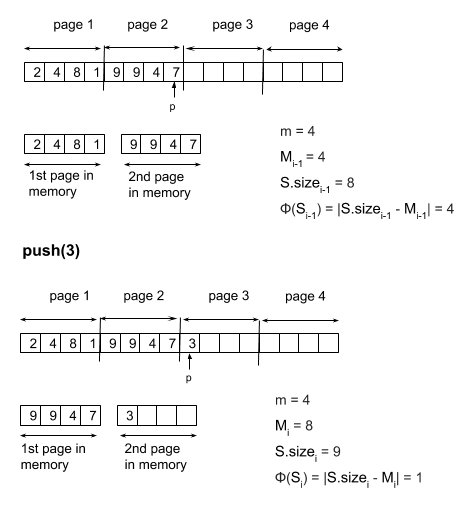

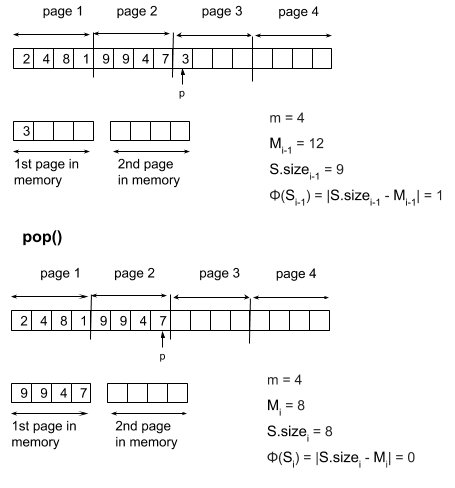

If you are not familiar with potential functions in amortised analysis, now is the time to read this post. For this problem, we are going to define Φ as Φ(S) = |S.size - M| where M is the last visited multiple of m (in other words, the index for the beginning of the last loaded page). Visually you can imagine the potential value to be the “distance” between the current pointer p and the index of the beginning of the last loaded page. When we are at a distance of m from that index, we are able to “pay the price” for a disk access.

First of all, let’s check that this Φ works as a potential function. We have the requirement that Φ(Sn) >= Φ(S0) for any n. For the empty stack S0, the most recently visited multiple of m is 0 so we have trivially Φ(S0) = 0. Since Φ is an absolute value, any value of Φ will be greater or equal to 0, which is all we need to prove the suitability of Φ as a potential function.

Which amortised cost does it give us for a PUSH or POP operation?

We have:

ĉi = ci + Φ(Si) - Φ(Si-1) = 1 + |S.sizei - Mi| - |S.sizei-1 - Mi-1|

To compute the |S.sizei - Mi| - |S.sizei-1 - Mi-1| term, we need to consider two cases, the case when we are pushing/popping inside one of the two currently loaded pages in memory and the case when we access the disk to load a new page.

When there is no disk access, the last loaded page is the same before and after the operation and we have therefore Mi equal to Mi-1. S.sizei has either incremented by one (PUSH) or decremented by one (POP), therefore the quantity |S.sizei - Mi| - |S.sizei-1 - Mi-1| is equal to either 1 (PUSH) or -1 (POP). That gives us an amortised cost of ĉi = 1 + 1 = 2 for PUSH and ĉi = 1 - 1 = 0 for POP.

When there is a disk access, let’s consider PUSH and POP separately.

For PUSH, we are adding an element at the beginning of a new page which needs to be loaded into memory. Mi is the index for the beginning of the newly loaded page and we have S.sizei = Mi + 1, and therefore the quantity |S.sizei - Mi| is equal to 1. S.sizei-1 is equal to S.sizei-1 and Mi-1 is the beginning of the last previously loaded page, which is saying Mi-1 + m = Mi. We have then |S.sizei-1 - Mi-1| = m. That yields us an amortised cost of ĉi = 1 - m which is constant.

push on a stack introducing a disk access with the two-pages implementation

For POP, we are removing an element at the beginning of one of the two currently loaded pages, and loading the page that comes before it. Mi is the page we are popping from and Mi-1 is the newly loaded page, which means Mi + m = Mi-1. S.sizei-1 is the size of the stack before popping the last remaining element which means S.sizei-1 = Mi-1 + 1, which gives |S.sizei-1 - Mi-1| = 1. After popping, S.sizei = S.sizei-1 - 1 = Mi + m, which gives |S.sizei - Mi| = m. That yields us an amortised cost of ĉi = 1 + m which is constant.

pop on a stack introducing a disk access with the two-pages implementation

That’s it!

With the potential function of Φ(S) = |S.size - M| we have proved that the amortised cost of both PUSH and POP was constant with the two pages implementation. Visually you can see that our previous boundary problem has been solved, as a push following this pop would not incur any disk access.

It’s nice that a small adjustment in the stack implementation allows us to change the worst case complexity in such a drastic way. This is an application of amortised analysis where it helps to “visualise” the operations to make sense of the maths.